THE THORAX.

Detailed Description—Legs—Wings—How used in Flight—Hooking together—Employed for Ventilating.

The thorax of the bee is divided into three sections, or imperfect rings. Of these, that nearest the head is called the pro-thorax, the middle one the meso-thorax, and the hindmost the meta-thorax. To the first of these are attached the most forward pair of legs; to the second, another pair of legs and one pair of wings; to the third, the last pair of legs and the other pair of wings. These organs of locomotion constitute, in fact, all that is worthy of special interest in this segment of the body, and we will, therefore, give a short account of them.

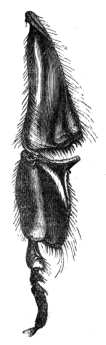

The legs of all insects consist of five parts, or joints, and in the case of the bee they are not only the means of walking or crawling, but, like some of the head organs of which we have spoken, serve several purposes. The first of the leg-segments is called the coxa, or hip, and is short and round, appearing, indeed, to be little more than the joint by which the limb is articulated to the body. The second is named the trochanter, and is very similar to the coxa. One purpose effected by these two portions is to give great freedom of motion to the whole member. Next comes the femur, or thigh, a longer and flatter division. This is followed by the tibia, or shank, a stouter and thicker division, which, especially in the hind-legs, becomes gradually wider downwards, and in the workers is adapted to a very special use, as we shall directly see. Then in succession we have the tarsus, or foot, consisting of five joints, the first very much stouter than the rest, and as long as the remaining four. It is terminated by a pair of hooked claws, with a cushion or pulvillus.

|  | |

| Fig. 28.—Lower Segments of Hind-Leg of Bee, Considerably Enlarged. | Fig. 29.—Complete Hind-leg Of Bee. |

We have already spoken of the remarkable apparatus found in the in the hind legs, adapted to the purpose of cleansing the antennæ. At the junction of the fourth and fifth segments (the tibia and the tarsus) of the hind leg of a worker a cavity is formed by the uppermost edge of the latter and the lower of the former. The cavity can be opened or closed at the will of the insect. Above this, on the outside of the tibia, is a pocket, or pollen-basket, lined along its upper edge with a row of lancet-shaped hairs, which aid in detaining the tiny balls of pollen, as they are successively deposited on the leg. Like a series of prong-tines, they can be pressed into the yielding bee-bread, and keep it from falling off; while, as they point downwards, they present no obstacle to the brushing off of the whole mass by the bee, on its return to the hive. The slight hollowing of the tibia and the tarsus at the approximating ends, affords more space for the gathered pollen, and also assists in its safe carriage to the cells.

The last joint of the tarsus is armed with a pair of double claws, and between them lies a hollow cup-shaped cushion, somewhat like that which enables the house-fly to walk on glass or other very smooth surfaces, only that the pulvillus of the fly is double. The edge of the cup is fringed with ciliæ, or very minute hairs, of such delicacy that a powerful lens is required to see them. Under the microscope, the object is one of great interest.

The claws serve for hanging from the roof or sides of hives, and for clinging to each other at swarming or wax-making times, the cushion for walking on smooth surfaces. It is worthy of remark that all the joints of the legs are covered with hairs more or less stiff, and all pointing downwards. Their uses are to collect pollen, and to act as brushes and combs to all the external parts of the body, which need constant cleansing from flower-dust, and other matters less useful to the bee.

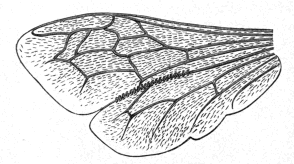

Fig. 30.—Wing of Bee.

Passing now to the wings, new marvels and beauties await our observation. These organs are four in number, the forward pair being considerably larger than the hinder. Each wing consists of a double membrane, dotted all over with fine hairs, whose purposes are to protect the delicate structure from wet, and from particles of various kinds which would adhere to it, and injure its surface. As a support for this expanded tissue, there is a ramification of stronger material, constituting nervures, and acting like the ribs of an umbrella. With these are associated air-vessels, or tracheæ, for the circulation of air, and, possibly, to assist in giving buoyancy to the organ. By another set of tubes a portion of the nutritive fluid is conveyed to certain parts of the wing, though no general circulation seems to take place in it. The substance of which the expanded portion, as well as the nervures, is composed, is very tough, and, as our readers may remember, the natural order to which the bees are assigned is named Hymenoptera, from the strongly membranous wings they possess.

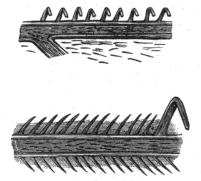

We can readily understand the importance to these insects of having their organs of flight powerful, and yet not weighty, tough without being clumsy. Considering the length of their daily journeys, and the constant and rapid movements they require to make, we easily discern how well suited to their needs is the structure of their wings. But we must call attention to a remarkable provision for the further utility of these organs. Under a lens of medium power may be seen, along the anterior edges of the hind wings, a series of booklets of hair, while on the posterior edge of the front wings is a rib, or bar, which the booklets can grasp. By this means the two wings, when used for flight, become practically one, thus presenting unbroken resistance to the air, and, in consequence, greatly increasing the power of propelling the body. When at rest, the unhooking of the edges enables the wings to be folded out of the way—no mean advantage in the crowded hive.

Fig. 31.—Hooklets of a Bee’s Wing.

But there is a further benefit thus conferred on the insect. During hot weather, and when the population is very dense, ventilation is constantly and vigorously carried on by the workers, who, fixing themselves firmly by their claws to the floor-board at the entrance, some outside and some just within their homes, direct numerous currents of air into the hive. Of course there must issue a quantity corresponding to what is driven in, and thus a perpetual and free circulation is kept up. Now, if the wings worked independently, not only would a smaller quantity of air be affected by each stroke, but the two sets of motions would, to some extent, counteract each other. As it is, the hooked wings act like well-constructed and well-used fans. By the simple experiment of slitting such an implement down the middle, the comparative advantages of a broken and an unbroken surface, for fanning purposes, can easily be put to the proof.

Thus, again, we are struck with the fact that the more closely we examine the organs of any segment of the body of the insect, the more reason do we find to admire the skill, and the care for His creatures, manifested by the infinitely wise and the infinitely good Maker of them all. Beauty, adaptation, perfection, are the words which are continually suggested to our minds by the contemplation of the structure of the bee.